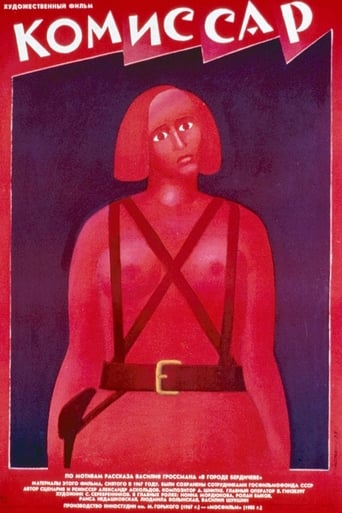

Klavdia Vavilova, a Red Army cavalry commissar, is waylaid by an unexpected pregnancy. She stays with a Jewish family to give birth and is softened somewhat by the experience of family life.

Similar titles

Reviews

It is understandable why Commissar was banned at its original 1967 release. Chronologically one of the latest films that can be classified as a "Thaw film," it takes the theme of the "individual over the collective" and extended it into dangerous, perhaps even un-Soviet territory. Despite deStalinization, the Soviet Union and its Communist ideals still stood—the collective was still to be seen positively, and the pure, militaristic attitude of the people was still important. By introducing Commissar Klavdia as an emotionless, militaristic "maiden" with male mannerisms at the beginning, and proceeding to reveal her personal, human side through her feminineness, pregnancy, and change of clothing as she was cared for by a Jewish family, the film interprets the Revolution as a "softening of Communist values." By changing Klavdia from the officer who ruthlessly sentenced a Red deserter to the tribunal at the beginning to being a scared, doubtful mother who seemed unsure of whether or not the new regime would bring "trams and success" when the idea was challenged by Yefim, Commissar, is questioning the validity of Leninism altogether! It becomes a defiance, not a "Thaw" reinterpretation, which is why it likely got banned. Another huge factor to its banning may have been the heavy sympathy for the Jewish faith that it evokes—anti-Semitism was prominent in the Soviet Union even after Stalin. Once it was released under Gorbachev however, the film was allowed to intrigue viewers with its whirling camera shots depicting Klavdia's flashbacks, and its interest in the effects of the Revolution on the psychology of children, by showing how messed up kids got under switching regimes. Understandably banned during its time, but it is a good film about the Revolution nonetheless.

From staunch militant to sensitive mother, Vavilova's search for self-identity is one that creates meaningful stories, both internally and externally. She is a very curious character. With masculinity and devout patriotism as two of her defining qualities, she does not subscribe to the typical female persona (at least in the beginning).Each quality creates a thought provoking dynamic for how she faces internal and external wars. Her internal war is pregnancy. As the child grows within her poses a threat to her masculinity, a subsequent external war is createdthat is, the child additionally poses a threat to her patriotic rank as Commissar. Although both wars throw her life into a state of imbalance, they also help develop her in becoming a more volitional and rounded character. In particular, her internal war creates maternity and sensitivitytwo qualities that lacked in her previous commanding status.She acquires both qualities after giving birth; this is depicted when singing a lullaby to her sleeping babe as well as when emotionally breast-feeding him (two actions which run contrary to her initially bleak and cold persona). Her external war (i.e. love of country), so too created by the pregnancy, introduces the most difficult challenge she has to face in the film: the choice of whether to marry herself to her country by divorcing from her child, or keeping her child and ridding her patriotism.What draws her to eventually side with her country is a series of haunting flashbacks and clairvoyant visions. In one specific moment while suffering through the birthing process, her mind flashes to a dreary landscape filled with military soldiers, who, like herself, struggle to push a heavy piece of artillery up the side of a steep and sandy hill. This image evokes at least one particular meaningone which acts like a stepping stone to help Vavilova make her final decision when giving up her child: The collective group pushing the machine uphill is a type of not only the communist ideals that Vavilova stands for, but is also a metaphor for the strenuous birthing process itself. In other words, the birth of a child and the birth of a nation are equally painstaking tasksboth which require exertion (i.e. masculinity) and loyalty (i.e. patriotism).The flashback ends with her waking up in panic, repeating to herself several times: "Stop torturing me." These words speak on multiple levels. In one sense, she is tired of being mentally tortured from the government that oppresses her with stringency. In another sense, she is tired of being physically tortured during the birthing process. Rich is the emotion and meaning of this flashback, and consequently it later leads to an extremely significant clairvoyant vision.During this vision she witnesses the forthcoming holocaust of WWII. She sees herself with child swaddled in arms, shuffling amongst a sheepish group of Jews as they wander to their death chambers. Reluctant to follow what she sees, it's as if she's asking herself while in vision, "Is this my fate?" Her subtexual obstinacy kicks in: "No, it can't be." She is the author of her choices and will not be subject to any deterministic beliefs. She feels she can change this outcome, but she must act now. However, the choice to act is a difficult one given her present circumstance. What choice does she make: raise her child or fight for her country? She cannot do both, for by focusing on one the other is inevitably sacrificed. Where, then, is optimism to be found in her utterly bleak and tortured world? The aesthetics of the film help contribute to this bleakness by the director's choice of shooting the story in black and white. Only in a world like Vavilova's are colors of the rainbow absent. The black and white look is a reflection of the coldness she feels inside, empty of any optimism. Interestingly enough, however, the Jews surrounding her in vision seem to be optimisticthey raise their arms in an almost dance-like ritual, knowing full well that death will soon embrace them all. She steps back nervously. Her body language has spoken. She remembers back on the corrupt youth that exist in her presentthe ones who so ignorantly mimic their corrupted eldersand feels an obligation to save the youth, and particularly her own child from such corruption. Although most of this is more or less implied, I strongly believe that this extraction is highly plausible given her final decision.She does not abandon her child, though some may argue so. She leaves her child in the hands of a very nurturing family; ones who she could trust since they too had nurtured her during her period of birth and even rebirth. Holding the confidence that her child will be safely watched after, she returns to her former state of balance by joining the war effort. She has rediscovered her meaning, place and identity in life: she is a warrior. Her life cannot be lived in fairy tales, like Yefim suggested when turning the war into a theatrical play for his children. Her life must be lived in truth and in truth only. That is the film's predominant theme: Despite how ugly the truth of reality iseven during times of war and tortureit must be embraced and dealt with; not thrown to some fantasy that creates false optimism. By living in a fairytale, she potentially falls prey to becoming a victim of the holocaust; by living in truth, she attempts to reverse the effects of such an outcome by fighting the monster of war.

Don't be tricked by the rating. This movie is wildly, unforgivably underrated on IMDb. To speak of its beauties would take me volumes. Suffice it to say: find it, if you can (it may be still available in good video stores, on VHS) and be enthralled by one-of-a-kind movie. As opposed to overrated 8+ 9+ c... like American Beauty or the Korean Oldboy and other movies full of either vapid pomposity or of guts and gore and blood and nonsense, Komissar is an extraordinarily beautiful and fluent meditation on human nature, war, religion, childhood, good and evil. Miss it at your own peril.10 out of 10

Throughout the movie, `Commissar', the innocence and naivety of the children allows them to be used as a medium through which many emotions can be conveyed. Sheltered from reality by their youth, the actions of children reflect their environment, unhindered as they are by experience, opinions, or understanding. The actions of a child are not filtered by taboos; the actions are pure and unadulterated regurgitations of the world around them.The example that stands out the most in the film is that of the playful pogrom. The actions of the three children, taken against the fourth, are a horrible reflection of the world they live in. However, this is not the only such example. In fact, the same concept, used in the very next scene, shows a beautiful reflection of the strength and courage of a family caught in the maelstrom. As the bombs begin to fall, and the children all begin to wail within the cellar, it falls on Efim to hold everything together. He does this in an incredibly powerful scene, standing up in the middle of his family and beginning to dance. Instinctively the children stand up to join their father in an act they are obviously as familiar with as the pogrom, and are placated by mimicking the ritualistic, soothing moves of their father. Whether or not they understand the significance of the dance, just as they may or may not fully understand the pogrom, is irrelevant to them. All that is important is that it and their father are there to give them comfort. Through the same general device, two very different ends are achieved. Many responses stressed the horrifically moving quality of the pogrom scene, but fail to mention the beauty and hope of a father dancing with his children, while the world rips itself apart around them.