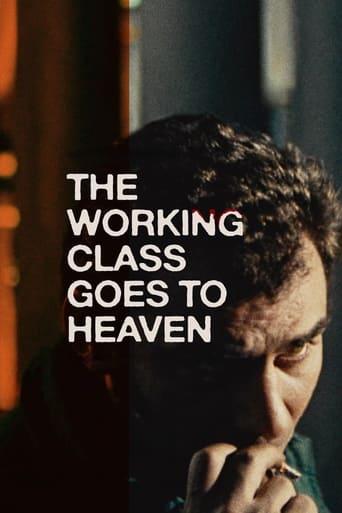

After losing a finger in a work accident, an Italian worker becomes increasingly involved in political and revolutionary groups.

Reviews

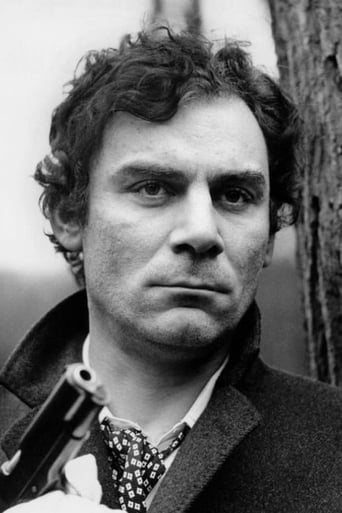

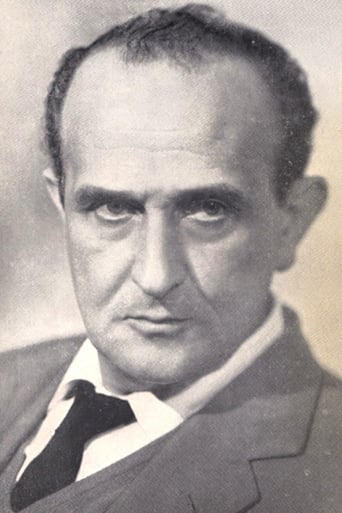

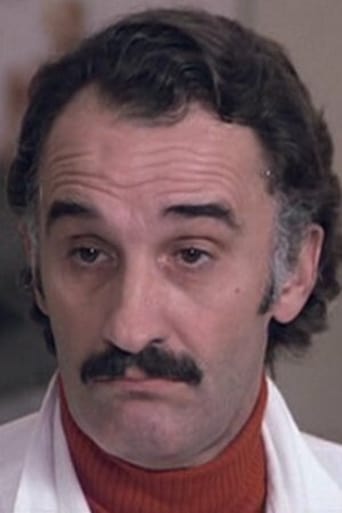

A diligent blue-collar worker Lulù Massa (Gian Maria Volonté) is averse to rebellious fractions within his working place and students who express their resentment of overwhelming physical labour which Lulù and co-workers are constrained to do in factories. Notwithstanding, one day, once he loses his finger in his factory and discerns the first symptoms of madness in his behaviour, he becomes involved in protestations which the scathing board of directors frowns upon This is a politically-tinged, existential drama par excellence which succeeds in being both insightful and poignant in its exploration of human condition in the Italian working class whose members are destined for solely biological existence. The stark portrayal of the pointlessness of life reminiscent of Woman in the Dunes (1964) by Hiroshi Teshigahara. Mr Petri, whose political propensities are fully evident here, passionately crafts this material and engrossingly displays the everyday dilemmas of physical labourers whose actions come to eating, drinking and doing their work which is humiliatingly and moronically simple. The frequent juxtaposition of a man and a factory infuses into this film gloom and dreariness which is difficult to bear with. The indication that one might sweep away the meaningless of an individual only through sexual consolation is very disquieting and the depiction of the sombreness and the repetitiveness of each day of life solidifies the sepulchral tone. Just like Petri's earlier I giorni contati (1962), The Working Class Goes to Heaven is a blend of existentialism and neorealism polished to perfection in Petri's hands whose meticulous stylization renders the concept as sulky and austere as the sterile, industrialized decor of Il deserto rosso (1964) by Michelangelo Antonioni. Lulù Massa – the main character of this flick –is the outcome of the mechanization of the unit whose productivity is the only value for his employer. Lulù is the most assiduous worker which arouses abhorrence in his colleagues. He does not attach any great importance to his mental and physical health and he thinks that there is no big difference between dying in his factory and somewhere else. Initially, he cannot comprehend why everybody is against him, but once he accidentally loses his finger and notices that he embarks on following the lane of insanity through his obsessive demeanour towards order, he regains his sight and perceives the world differently.Even though The Working Class Goes to Heaven is not as Kafkaesque as The Assassin (1961) and Investigation of a Citizen Above Suspicion (1970), it appears to refer to Kafka's short story A Report to an Academy which is about an ape which learns to behave like a human. During his visit in a mental institution where he meets a veteran ex-blue collar Militina, Lulù is shown an article from a newspaper which recounts a story of a chimpanzee which believes in its humanity. Petri seems to liken the Kafka's ape and Lulù, notwithstanding, whilst the monkey from Kafka's tale obtains a new identity by approving of milieu repressing it and adjusting to its new entourage, Lulù Massa restores his personality on account of a calamity and the stifling milieu of his factory, hence, just like in case of Investigation of a Citizen Above Suspicion, Mr Petri once again turns the world of Franz Kafka upside down.Besides dilating upon the harsh fate of the working class, the director likewise hints at the exploitation of labourers from the poverty-pervaded southern Italy. Other Italian intelectualists such as Pier Paolo Pasolini also alluded to this phenomenon. Mise-en-scene by Elio Petri is exquisite and thoroughly unfaltering in its exposing the major concept. The resonance of his last acclaimed opus is indubitably enormous. Apart from delving in the issue of alienation and helplessness, the highly flamboyant subplots reinforce the main theme and endow it with abundant background and owing to relatively deliberate pace, the content is never lunged too hastily.The acting is simply excellent throughout the entire motion picture. Gian Maria Volonté conveys to his role such a great portion of galvanizing rampage that he ravishes with his commitment to his part which might be one the most powerful in his utter career. There are other phenomenal performers in the cast, such as facially distinctive Mariangela Melato, Flavio Bucci, and last but not least enthrallingly convincing Salvo Randone.The subsidiary cinematography by Luigi Kuveiller is obviously a determinant of quality, but what emerges from his beauteous takes of impoverished flats of physical workers is the mutual sway between Bertolucci and Petri. Bernardo Bertolucci conceded his fascination with merging existentialism and neorealism in I giorni contati by Petri, and Petri seemed to be enchanted by the lighting and visual aspect in The Conformist (1970) which was visible in the case of The Working Class Goes to Heaven. The shots of indigent flats framed with gleams of blue radiance constitute a chilly, bitter aftertaste which exerts a beneficial impact on the other ingredients. The symbiotic soundtrack by Ennio Morricone is one of the most idiosyncratic elements and the flick would feel totally different with a distinct piece of music from another composer. Mr Morricone provides us with one of his most unusual and characteristic creations which is rapid, aggressive, contextualises with the ensemble absolutely perfectly and reverberates like a genuine machine.Though the movie overzealously strives to inculcate Marxist doctrines in its viewers and Petri's appeal to social alignment is displayed here, it does not modify the fact that it is an exceedingly significant film which has to be analysed, discussed and considered to be a major motion picture which auspiciously encases the atmosphere of those days filled with protestations, but also exhibits a timeless struggle of a man attempting to retain dignity, despite difficult living conditions and tough work.

Elio Petri directs his frequent collaborator, Gian Maria Volonte, in a drama about Lulu, an Italian factory worker contemptuous of his colleagues' attempts to get better pay and working conditions through their union. Lulu prides himself on being a productive worker, and the bosses praise him for his almost superhuman devotion to work. In spite of that, Lulu is just another worker scraping a meager job, living in a crummy apartment, with a woman he doesn't love very much. His personal life seems to amount to visiting a former work mate, who's now living in a mental hospital.Lulu's outlook, however, changes when he loses a finger in a factory accident. Although the accident doesn't leave him disabled, it makes him spin out of his numb existence as he gets more interested in the unions' struggles. But if before he was indifferent, now he starts getting involved with radical extremists preaching a new social revolution, instead of the more moderate but realistic unions.The movie is interesting because of the way it portrays the schism between unions: on the one hand, there's the traditional union, composed of workers, who just want to improve their lot, get a payrise. And then there are the Marxist-Leninist students and intellectual nutjobs who never put a foot inside a factory and who want to blow society up and rebuild it from the ashes. Petri is deservedly critical of the latter.The movie shares similarities with neorealist cinema in the way it portrays the squalor and working conditions of ordinary people, but Petri isn't particularly soft on the working class. Their inability to get organised, their own selfishness, and the lack of credible leaders to inspire them, is nicely dealt with in here. The viewer expecting just propaganda will be disappointed.Gian Maria Volente delivers a fine performance, especially in his mad outbursts of rage and madness. Petri has directed better movies, but The Working Class Goes to Heaven manages to tackle many of the issues in his oeuvre and so is also an indispensable movie for fans.

The Spirit of Social Justice of the May '68 uprisings is still very much alive in this heavy-going but compelling parable of the rise and fall in the fortunes of an Italian factory worker dubbed Lulu (Gian Maria Volonte'): starting out as the Boss' darling for being the exemplary employee and pacesetter of the company, the loathing of his co-workers (who despise him for how his excessive zeal makes their own lackluster performance look bad in the eyes of the manager) and his female companion Mariangela Melato (who never gets any piece of the action at night because of his constant fatigue) eventually gets to him one day with the result that he loses his concentration at work and suffers the loss of a finger in an accident. This changes his whole outlook on life as he becomes engrossed in an extremist workers' union, finally makes love in his car to a virginal female co-worker/union member he is obsessed with, is quitted by his consumerist hairdresser companion and his surrogate son and, when he is given the sack at work and is on the point of selling off his belongings, another more moderate workers' union comes to his aid by winning him his old job back. Although there is obviously much footage here of socio-political discussions, scenes of picketing and police riots, confrontations between diverse unions, etc., the film also has that winning whimsical streak promised by its title and exemplified by amusing episodes in a mental institution (where Volonte' visits his cracked-up ex-colleague Salvo Randone), the quasi-surreal sequence of Volonte' taking it out on all his useless possessions (including a giant inflatable doll of Scrooge McDuck!), and the concluding description at the assembly line of the titular incident itself which Volonte' had in a dream the previous night. Ennio Morricone's inventively 'metallic' music underscores the robotic gestures of the factory workers who, despite slaving eight hours a day at their machines, are not even aware what becomes of the parts they produce! While the film may seem overdone and dated in today's apathetic age, it clearly hit a nerve at the time of its release winning a handful of international awards including the Palme D'Or at the Cannes Film Festival.

The movie has a great power, first of all he gives to Lulu a mechanical soul, the camera follows his unhuman movements caused by too much work and let us understand something strange like madness. Then we have the political part: outside the factory people are pemanently screaming verses against owners like another machine that creates words, but the real impressing moment is inside the factory where man and machine became the same things so that the camera let us see the hidden mechanical part and the human movements togheter; the music too (by Ennio Morricone) adds a sense of robotic condition.